Back in 5th grade, I took a test that would change my weekends for the next few years: the Deneyap E-Exam. You might not be familiar with Deneyap, especially if you don’t speak Turkish. The name itself is a pun, combining the words for “experiment” and “do.”

Deneyap is a project of The T3 Foundation aimed at educating talented young people in technology. Its goal is to create the driving force of Turkey’s National Technology Initiative. For me, Deneyap was the place I happily went to almost every weekend for about three years. It’s a program where students aged 9-10 (or 13-14 for the high school program) learn about the world, from designing 3D models to debating the ethics of nuclear energy. The curriculum is designed to help children use science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) to make the world a better place.

Students are “cherry-picked” through a two-part selection process. The first part is a written test on math, culture, algorithms, and science. This is relatively straightforward compared to the second part: the interview. In this stage, students are given a problem—for example, building a cargo boat that must carry 50g of cargo across a pool of water. They’re given a week to research a solution, after which they are provided with equipment like cardboard and DC motors to build a working prototype. They then present their solution to a jury. The most common pitfall for students is either failing to create a working solution or struggling during the presentation. If a student passes both exams, they are officially accepted into Deneyap.

The Deneyap curriculum covers 11 main topics: Design and Production, IoT, Coding and Robotics, Nanotechnology and Materials Science, Software Development, Cyber Security, Energy Technologies, Advanced Robotics, Aerospace Technologies, AI, and Mobile Application Development. These courses are a mix of online videos, interactive classes, and face-to-face workshops. All topics conclude with a project that every student must complete using the tools available in the Deneyap workshops.

After the two-year educational program, students enter a final competition. They form teams of three to four people and choose from a wide variety of topics provided by Deneyap to build a project of their own choosing. Their challenge is to develop a prototype solution using the one and only Deneyap Kart. This development board, powered by the ESP32, is a staple of the Deneyap education. While it doesn’t differ much from other ESP32 boards, its occasionally unclear documentation and error-filled libraries teach users a valuable skill: patience.

During the five-month competition period, each team is assigned a mentor who guides them. The teams also elect a leader to arrange meetings and write reports. They meet online twice every two weeks and in-person once a month to present their progress to a jury. After five months, the teams are invited to a final presentation where they demonstrate their working prototypes and display a poster about their project. The jury rates the teams and selects three winners: best prototype, best presentation, and best poster. These winning teams present their solutions on stage to all the other participants and Deneyap officials. All students who make it to the final presentation receive their graduation papers a week or so later.

And that was my Deneyap journey, from start to finish. I passed the initial exam and interview, completed the education, and ultimately graduated.

In September 2024, my Deneyap education officially concluded. This was also when I started 8th grade, which meant I had very little free time due to studying for the High School Entrance Exam. Luckily, the competition didn’t start until December, giving me a chance to work efficiently. My team and I chose Wearable Devices as our topic in our first meeting. After a long discussion, we decided to create a modular smartwatch. Thus, SenSaat was born: the customizable watch, powered by the Deneyap Kart.

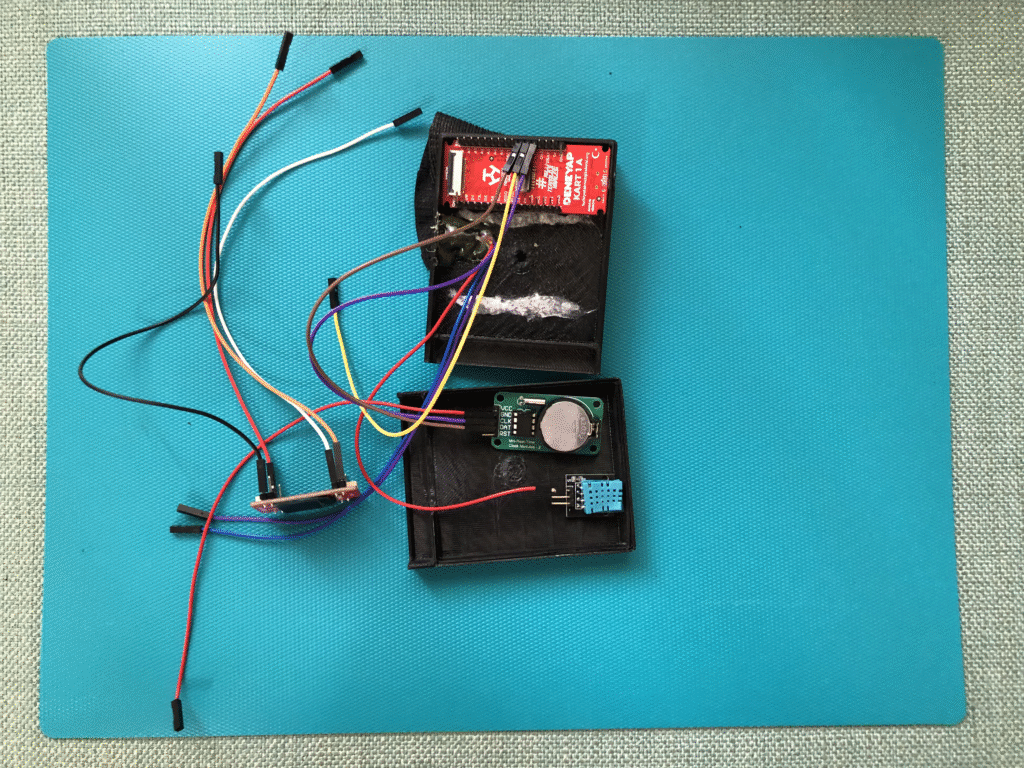

We faced some major challenges. Our components were fitted inside a 3D-printed Commodore 64 cartridge, and the RTC controller would sometimes reset itself. But I found a solution. My first step was to code a simple program—though it was more of a guardrail to prevent crashes and display the UI. Beyond showing the date and time, the UI is used to monitor and display data from the connected sensor. Once that was done, the only thing left was to cram the components perfectly inside a slightly modified Commodore 64 cartridge shell without using any glue.

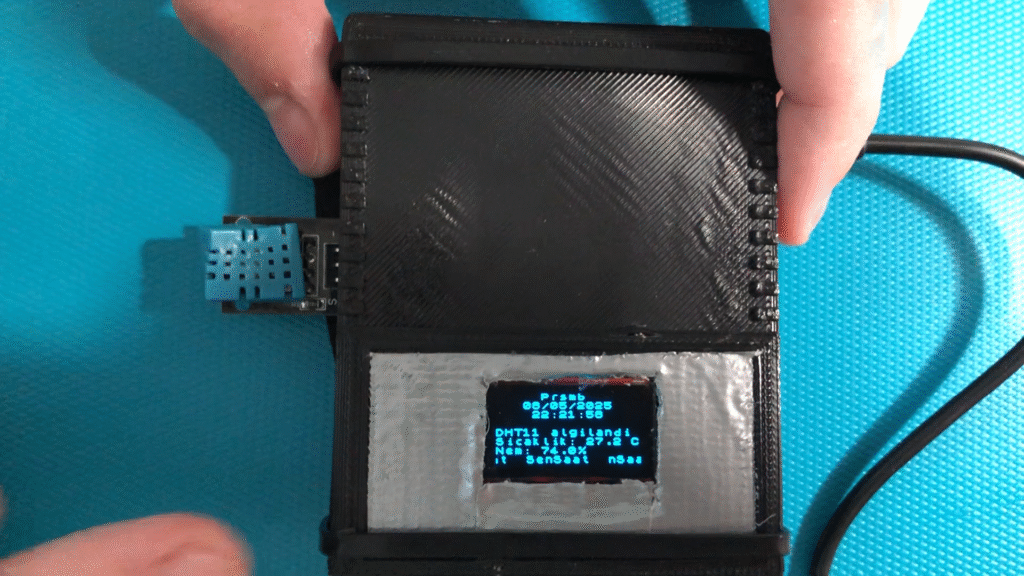

The DHT11 is connected on the left port, the case is held by cable ties for easy access to the internals

The DHT11 was connected to the left port, and the case was held together with cable ties for easy access. What was truly amazing about this fully functional prototype was that any component, including the DHT11, could be hot-swapped. I could take the display out and plug it back in, and it would still show the UI. This tiny feature was so cool that the watch doubled as a fidget toy for me.

The jury evaluated our team first. We had them wear the watch, then plug in the DHT11 sensor. They blew on it and saw the moisture level rise on the screen. This demonstration, which showed the full potential of the Deneyap Kart and its compatible sensors, earned our team the Best Prototype Certificate.

Wondering how he got here, probably

It took me about a week of working in my spare time to prepare the prototype from start to finish. I put in my best effort, and this is what came out of it. It was a very fun experience to pull off, especially since our competition was mostly made up of cardboard models and a single RC car. The whole experience showed me a lot about the importance of team effort and building a product from scratch.

Overall, I really enjoyed my time in Deneyap and learnt a lot about life itself. I hope that it continues for many years to come.

You can find the firmware on my GitHub

Special thanks to my teacher Yusuf Kirik from Pendik Deneyap, my teammates, and our mentor Efe Kaan Yıldırım.